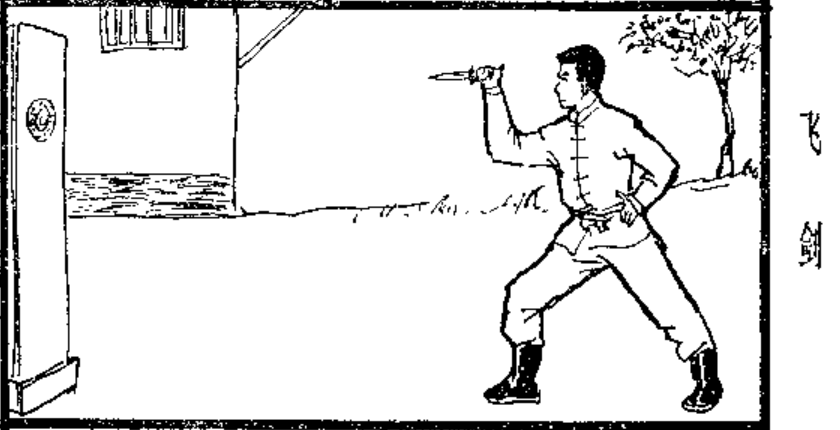

The following is a description of Feijian 飞剑, with content sourced from two nearly century-old Republican-era Chinese books: The Secret Techniques of Practicing Hidden Weapons and The Complete Transmission of FEIBIAO, FEIDAO, and FEIJIAN: Hidden Weapons Anthology. The style of written Chinese from that period differs significantly from modern Chinese. After careful research and verification, our team has translated the following English description based on those original texts.

Special thanks to Chief Lao Qiu 酋长老秋 for providing the original source materials and related assistance.

Note: In Chinese, the word “sword” (剑) can refer not only to long swords but also to short double-edged daggers. In the following text, both flying dagger and flying sword refer to the same weapon — a double-edged dagger measuring 26 centimeters in length.

In the world’s discussions of flying daggers (Feijian), tales often veer into the fantastical — with claims of forging swords through mystical breathing techniques or transforming pills into blades, scattered throughout various old records, as though such things truly existed. In modern wuxia novels, these notions have been further romanticized: a flash of blue light, and an enemy’s head falls a hundred paces away. Whether or not such things ever truly happened is beside the point; even if they did, those mystical arts of inner breath manipulation stem from Daoist traditions and cannot be compared to ordinary martial arts.

The flying daggers I speak of is not imaginary but a real hidden weapon, something one can actually learn and practice. Its origins trace back a long way. In the Tang dynasty, there was a figure named Ye Fashan, styled Daoyuan, a famed hermit who lived in the Maoyou Mountains near Songyang. A master of Yin-Yang, divination, and incantations, Emperor Xuanzong of Tang once summoned him to summon the spirit of his lost beloved, Yang Yuhuan. Ye’s feats became famous for a time.

According to Kaitian Chuanxin Ji, Ye Fashan possessed a mystical art. One day, while meeting officials at Zhenyuan Temple, a man claiming to be Qu Xiucai barged into the gathering uninvited. Handsome and eloquent, he made an impression. Ye picked up a small sword(In Chinese, a dagger is also called a small sword.) and hurled it at him, striking him down on the spot — revealing the intruder to be nothing but a wine gourd concealing fine liquor. Regardless of whether this incident involved magical strength, the record clearly states Ye used his hand to throw a tangible small sword, not an immaterial sword summoned by breath, thus aligning with what we now call flying swords in hidden weaponry, and not with swordsmanship-based flying sword fantasies. Hence, I assert that the method of throwing small swords existed as early as the Tang dynasty. Though its origins before that are untraceable, it is no stretch to credit its popularization to Ye Fashan, a widely respected figure of his time. Surely, among the capital’s martial enthusiasts, many would have taken to emulating him.

After the Tang dynasty, flying swords became a fixture within the world of hidden weapons. In the Song dynasty, the use of hidden weapons flourished, with countless ingenious contraptions and mechanical devices that improved ease of use, accuracy, and range — like foot bows and sleeve arrows. Consequently, flying knives and flying daggers temporarily declined in popularity, passed down sporadically like faint threads through the generations.

In the early Qing dynasty, a man named Zhang Huaiwu established the Xinglong Escort Agency by imperial decree, specializing in protecting merchants and travelers. He gathered talented warriors from all directions, like rivers converging in the sea. Among them were many men of rare skill and unusual abilities, convening in one place to exchange techniques, particularly those of hidden weapons, to which they devoted exceptional effort. At that time, an armed escort (biaoshi) was expected to possess one astonishing skill — not only to impress others but also to leave a personal mark: so that anyone encountering a particular hidden weapon would instantly recognize whose hand it came from. This helped prevent trouble and ensured safe passage. This is why martial escorts paid special attention to dart and throwing techniques.

Among them was a man from Hebei named Li, a disciple of Zhang’s, who stood out among Zhang’s followers for his skill with flying swords. On outings to the countryside, Li would casually throw small swords to skewer wild animals, always hitting his mark. One day, while deep in the mountains, the group encountered a golden leopard. Alarmed, the party armed themselves and attempted to drive it away, but the beast refused to flee and charged the men. Li quickly hurled a sword, striking the leopard’s left eye. Roaring in pain, the beast stood upright, and Li’s second sword flew — piercing its belly and felling it. The onlookers were awestruck and requested to learn his technique. Li, not overly secretive, shared it, explaining it had been passed down through seven generations in his family. His distant ancestor, a commander in the Qi Family Army, had acquired the skill from a mysterious stranger, using it to win many battles. Ever since, it had been carefully preserved and never casually shared.

From then on, people no longer called him by name but addressed him as “Swordmaster Li.” In truth, Li’s flying sword was a type of hidden weapon, not swordsmanship per se — though contemporaries calling him a swordmaster was a bit of an overstatement. At that time, any escort using flying swords was presumed to be a disciple of Li, and no one dared challenge them lightly, fearing the legend of the leopard-slayer.

After Li’s death, his dozen or so disciples could use flying swords but none matched his mastery. They kept to themselves, swore not to pass the technique lightly, and the number of practitioners dwindled. In the reign of the Xianfeng Emperor, there was a famed constable named He, who excelled at the art — able to hit birds and beasts within a hundred paces without fail. Thanks to this skill, he captured criminals without mishap and enjoyed a celebrated reputation for decades.

In his old age, one year when a provincial treasury suffered repeated thefts, He was summoned to investigate. The thief turned out to be a formidable opponent, and He was unable to best him in close combat. In the end, he severed the man’s leg with a flying sword and captured him. He too was a master of the art. But after that, few experts in flying swords emerged. Though some present-day hidden weapon practitioners claim proficiency, it’s doubtful that any possess the refined skill of Li or He. Still, with devoted study, it is not impossible to surpass the ancients.

On the Structure of the Flying Sword

Unlike flying darts or throwing knives, which come in numerous variations, the flying sword has only one form. A type of short weapon, it features a double-edged, sharp-tipped blade. In ancient times, swords were worn both for ceremonial display and emergency defense, later employed in battle. The flying sword is essentially a miniature version of a standard sword, identical in shape but much smaller.The blade measures 7 cun (25.8 cm) in total length. Its tip forms a sharp triangle, known as the Jian Tou (剑头), the most crucial part of the weapon, as sword techniques emphasize thrusting over slashing. The blade edges beneath the tip are thin and sharp, called the Ren (刃). The central ridge on both faces is the Jian Ji (剑脊).

At the junction between the blade’s end and its handle is a round handguard called the Jian Pan (剑盘). Behind this lies the handle, known as the Jian Jing (剑茎), ending with a small ring called the Tan (镡).

Dimensions:

● Tip (Jian Tou): approx. 0.5 cun (1.65 cm)

● Blade (tip to handguard): 4.5 cun (14.85 cm)

● Edge-to-edge width: approx. 0.5 cun (1.65 cm)

● Ridge-to-ridge width: approx. 0.2 cun (0.66 cm)

● Handguard diameter: approx. 1 cun (3.3 cm), thickness 0.2 cun (0.66 cm)

● Handle length: 2 cun (6.6 cm), circumference 0.5 cun (1.65 cm)

● Pommel ring circumference: less than 0.5 cun (1.65 cm)

Each flying sword weighed between 5 liang (160 g) and 7 liang (224 g) — about one-seventh to one-eighth the weight of a full-size sword. Hidden weapons prioritize portability: too large is cumbersome, too heavy hinders throwing.

Forging such a blade was arduous. Like the legendary swords of Ganjiang and Moye, it required years of repeated hammering and refining to turn crude iron into divine steel — able to slice through iron as if it were mud. The essential step was choosing fine wrought iron, smelting it once, then soaking it in a well or mountain stream for several days. It was then reforged and re-soaked repeatedly until all impurities were removed, producing a blade suitable for practical use.

The Tedojo-reconstructed practice flying dagger-Strom:

Video link about FEIJIAN:

https://youtu.be/CsvZGha3rfE?si=ygiSl8byy72tWodm