The following is a description of Feidao飞刀, with content sourced from two nearly century-old Republican-era Chinese books: The Secret Techniques of Practicing Hidden Weapons and The Complete Transmission of FEIBIAO, FEIDAO, and FEIJIAN: Hidden Weapons Anthology. The style of written Chinese from that period differs significantly from modern Chinese. After careful research and verification, our team has translated the following English description based on those original texts.

Special thanks to Chief Lao Qiu 酋长老秋 for providing the original source materials and related assistance.

There are many types of throwing knives — some are single-edged, some double-edged, and some shaped like a crescent blade. Different shapes require different throwing methods. Here, we will first discuss the double-edged type, commonly known as the “Willow Leaf Throwing Knife,” so named because its shape resembles a willow leaf.

The blade is about six inches long (≈ 19.8 cm), the handle about 1.7 inches long (≈ 5.6 cm), with a guard between them. The blade is narrower at the top and wider toward the base, closely mimicking the shape of a willow leaf. Both sides are sharpened, thin as paper, with a raised ridge running along the center of each side. The tip is extremely sharp, and the overall design is somewhat similar to a sword. The thickest part of the ridge is just over two millimeters. The blade weighs a little over three taels, the iron handle about four taels, and the guard—slightly wider than the handle—about two taels. Altogether, each throwing knife weighs around ten taels (≈ 320 g).

At the end of the handle are red and green silk ribbons, each about two inches long. These create wind resistance during flight to aid in aiming, much like the tails on a throwing dart. The knives must be forged from pure steel, with twelve stored in one scabbard—ideally made from sharkskin. The scabbard is divided into upper and lower rows of six knives each, tips pointing downward and handles exposed for quick access.

Carrying methods differ from those of throwing darts. Darts are worn at the waist, but the throwing knife scabbard is worn across the back. Right-handed users sling it from the left shoulder across to the spine, while left-handed users wear it from the right shoulder to the spine. There is no fixed rule for carrying concealed weapons; placement should be determined by the intended use.

The willow leaf knife’s killing power lies mainly in its sharp point. The dual edges have relatively little use, though sometimes an opponent who dodges the tip may still be cut. Fully using both edges for chopping or slashing in close combat requires deep skill—usually more than ten years of training. The knife’s weight and size are not fixed; if the practitioner feels it’s too large or heavy, it can be reduced, and if too small or light, increased. However, too light and small makes it hard to injure, while too heavy and large is burdensome to carry, so a balanced, medium specification is most practical.

Training Method for Willow Leaf Throwing Knives

Training differs entirely from that of throwing darts or arrows and is even more difficult. Power is delivered through only one method—yin shou (“inward hand”), a downward wrist-snap motion. Unlike darts, you cannot throw sideways or upward. Though there is only one throwing motion, hitting different targets remains challenging.

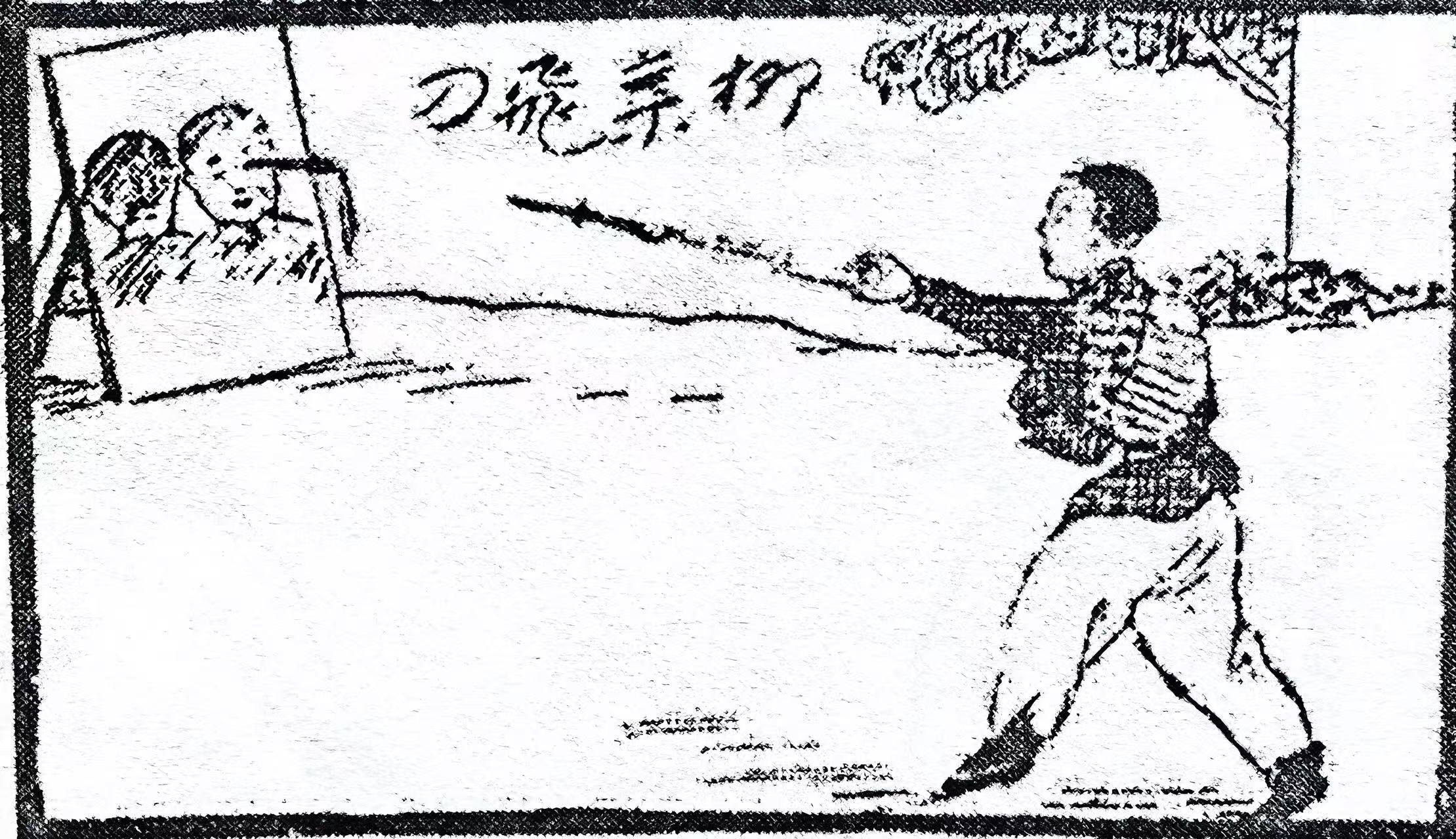

When using the yin shou motion, the knife is held by the handle and snapped forward and downward, relying on wrist force rather than a pushing motion like shooting an arrow. Because it’s driven purely by this snap, the knife follows a semi-circular path—a parabolic arc. As a result, when aiming, the tip must be aimed a few inches above the target so it drops into it from its highest point.

In the beginning, the target is the same as for throwing darts. Stand one zhang (≈ 3.3 m) from the target, draw a knife from the scabbard, aim, and throw with the tip about one inch higher than the bullseye. If you miss, throw the next one, repeating until all twelve are thrown. Then check your hit rate and analyze misses, usually caused by being too high, too low, too far left, or too far right. Practice morning and evening, each session with a set duration.

Once you can reliably hit the target from one zhang, move back several feet and repeat. The farther the distance, the higher you must aim the tip, which is simply the law of the parabola.

When you can hit accurately from one hundred paces (≈ 165 m), reduce the target size and continue until you can strike a spot less than an inch in diameter with perfect accuracy. Then you can change targets: draw a life-size human head and shoulders on a wooden board—one front view with full facial features, one back view with small circles marking vital points behind the ears and elsewhere. From one hundred paces, first train to hit both eyes, then the ears, nose, and facial points (such as tian ting, yin tang, and the temples). When you can hit the chosen point without fail from the front, practice the same on the back view until you can strike any chosen vital point at will. At this stage, the art of throwing knives is considered mastered. From start to finish, this takes at least three years.

Variations in technique and distance must be learned through personal experience. With practice, skill becomes second nature, and countless variations emerge naturally.

Scanned Copy of the Old Manual